The Barong Tagalog: From Fibres to Fabrics

Fibers are the building blocks of the yarn; yarns are the building blocks of the fabric. Making continuous yarns or threads from fibers is called spinning, which usually involves twisting a succession of fibers. Twisting makes the yarns stronger and more compact and thus more suitable for weaving. In silk yarns this process is called “throwing.”

Not all fibers, however, can be spun into yarns. Piña fibers, for instance, require a different process. They are knotted or tied from end to end to form continuous strands of yarns for weaving, a process requiring a lot of skill and time owing to the delicate nature of the piña fiber, which is thinner than a strand of human hair. Knotting one bas-ing, or 32 grams of loose fiber, can take up two weeks.

One marvels at the ease and dexterity of Aklanons who can tie the fibers as close together as possible so that the knots are almost invisible to the untrained eye. Up to the colonial times, knotting, however difficult, was just part of everyday household chores.

As mentioned earlier, weaving was a well-known craft in the archipelago long before Spanish times. Awed by the great quantity of cloths woven here, Francisco de Sande in his 1577 report, Relation and Description of the Philippine Islands, says, “All know how to raise cotton and silk, and everywhere they know how to spin and weave for clothing.” Obviously, Sande was unaware that the silk fibers were actually imported from China, although cotton abounded throughout the islands.

Filipinos worked two types of looms during the Spanish period: the backstrap loom, which is still used in textile weaving communities in Northern Luzon, Mindanao and Sulu, and the European-style upright, treadle or pedal loom, which the Spaniards introduced here to promote the manufacture of cotton for export to Europe and is today preferred by lowlanders.

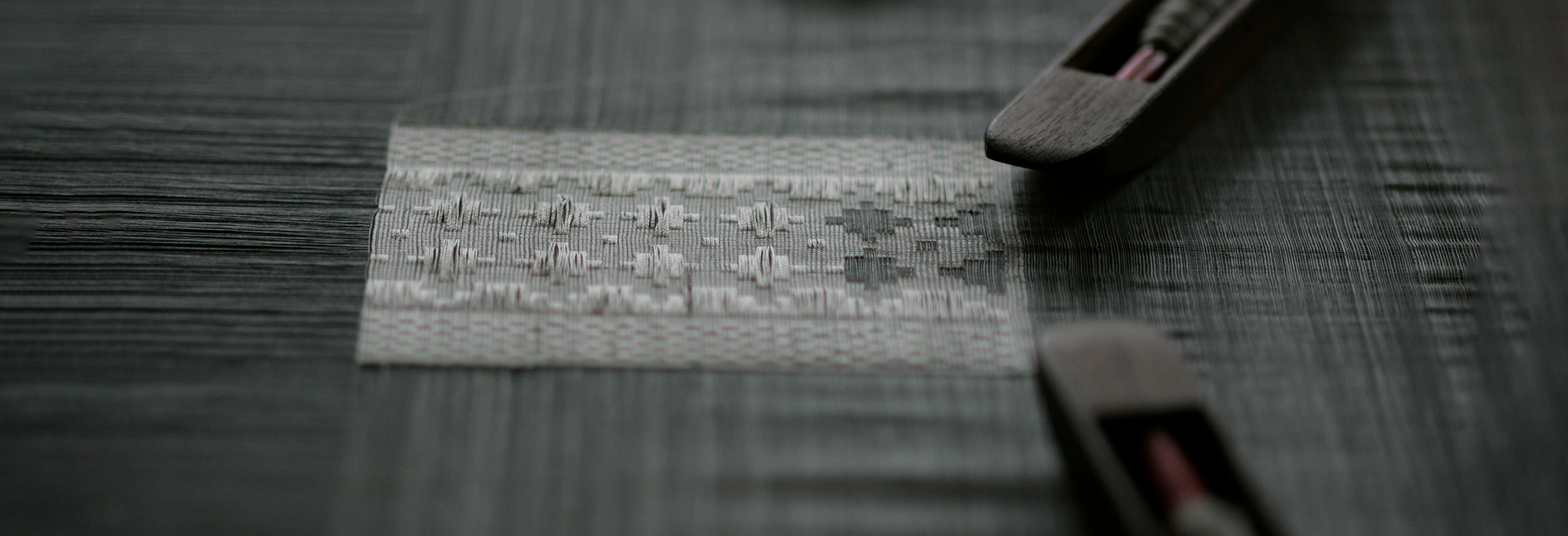

The weaving of piña and jusi and their mixture, piñaseda, is done on the treadle loom. In Aklan, the acknowledged center for the production of these fabrics, the device is found in practically every home in the province’s weaving towns of Balete, Banga, Lezo, Makato and Kalibo, which produce 35,000 meters of pure piña cloth alone annually.

The piña cloth used to be known as kalibo, as it was called in the Spanish period, indicating that the cloth originated from Kalibo, now Aklan’s capital. Piña weaving is an arduous craft. Two preliminary processes—pagsab-ong, or warping (preparing the yarns that run lengthwise), and pag-talinyas, or bobbining (winding the knotted yarn for the weft onto bobbins or spools)—may take as long as a week, depending on the length and width of the yarns being arranged on the loom.

Handling the piña can be exasperating. It breaks at the slightest pressure. Mallat says that to be able to work with the finest quality of piña, weavers needed to “place themselves under a mosquito net, for the threads . . . break at the mere movement caused in the air by a person walking.” Today’s weavers no longer have to do this.

To protect the piña from, say, human movement or sudden gusts of wind, weavers keep the loom in a special room. Philippine weather, however, remains a problem, according to Montinola. She says the best time for weaving the fabric is in summer, as piña fi bers tend to stick together during the rainy season and ungluing them causes more breakage. No wonder a weaver working a ten-hour day can produce only about 40 centimeters of cloth.

The newly woven piña cloth undergoes finishing touches—bleaching or dyeing—before it reaches the buyer. To bleach the fabric, the weaver soaks it in rice water, watered-down kalamansi (a Philippine citrus) juice or chemical bleaching solution, though traditionalists frown at the latter.

What constitutes good quality in piña cloth? Although the weaver still has the last say in this, a few guidelines from the Fiber Industry Development Authority’s Zeleña Dalida, fiber officer in Aklan, can help the inexperienced buyer tell good piña from bad. Good piña is distinguished by the following characteristics. The weaving is siksik, or tight, showing no spaces between the fibers and no loops along the edges. The strands of fiber are smooth and fine as is the cloth, so that knotting is almost imperceptible.

The desirable characteristics hinge on the three important stages in the production of the piña cloth: scraping, knotting and weaving, respectively, pagkigue, pagpanug-ot and paghaboe in Aklanon. Careful scraping produces fine, immaculately clean, lustrous fibers; perfect knotting ensures that no bumps roughen the otherwise satiny texture of the piña; and precise weaving turns out an evenly tensioned, flat fabric having no spaces between the fibers. Of course, it is assumed that only healthy piña fibers are used. Thus a beautiful piña cloth is the handiwork of a long, meticulous process requiring a great deal of patience, dedication and technical excellence.

The Aklanons have these virtues. Looked up to as role models in the industry, they have earned their reputation for their consistently excellent work, industry and perseverance—qualities that have endeared them and their products to designers, textile traders and barong boutique owners. Indeed, whenever one hears of piña, what immediately comes to mind is Aklan.

Being in an Aklan weaving community is like being in a community of craftsmen, where scrapers, knotters and weavers are engrossed in the singular purpose of producing the finest piña. Their skills have brought them to the farther shores of Negros Occidental, Negros Oriental and even Palawan, where they’ve spread their gospel to fellow weavers, so that today the piña has also become a byword for incomparable perfection in these places.

Related Stories

Threads of Time: Unraveling the Rich History of the Barong Tagalog

In the tapestry of Filipino culture, the Barong Tagalog stands as a distinctive thread, weaving…Embroidered Stories: The Cultural Significance of Barong Tagalog Patterns

In the world of the Barong Tagalog, every stitch tells a story, and the intricate…The Barong Tagalog: Classic Barong Styles

In a crowd of barong-clad men, pick out two barongs that are exactly alike. It’s…Draping Elegance: Famous Personalities and the Barong Tagalog

The Barong Tagalog, an embodiment of Filipino elegance, has graced the shoulders of numerous notable…