The Barong Tagalog: Early Beginnings

The barong tagalog is the upper garment worn on formal occasions by Filipino men (though Filipino women have long impinged on this exclusiveness).

Traditionally, it is a translucent tunic that falls mid-thigh and is slit on the sides; it has a collar and straight, long, cuffed sleeves. Its most distinguishing feature is the fine embroidery usually girding the garment’s opening from neck to waist. Almost always, it is worn hanging loose over the trousers.

Etymologically, barong derives from baro, the Tagalog word for male or female clothing. In turn, baro stems from the Malay baju, which has the same meaning. Inflected, it is a contraction of the phrase baro ng, meaning “dress of.” “Tagalog” refers to the ethnic name of one of the archipelago’s early settlers who lived in the lowlands of Central and Southern Luzon. In this context, barong tagalog literally means the dress of the Tagalog.

Over the years, as various other ethnic groups adopted the garment, it became a national costume and its parochial identity was supplanted by a more universal term: barong. Never mind if its abbreviated name didn’t have a direct object, like a name without a surname. To this day it flouts grammatical correctness. Of late, however, Filipino Americans, asserting their roots to distinguish themselves from other ethnic groups in their adopted country, have rechristened the garment with a patriotic name, barong filipino, thereby fixing its national character. Still and all, damning grammarians, most Filipinos call the garment barong.

The baro entered written history through the Chinese. The first positive mention of the Philippines as Ma-i or Ma-it is inscribed in a brief notice in the official Sung history in A.D. 982, when Philippine trading boats laden with valuable merchandise were recorded to have reached Canton, a southern Chinese port city. Chao Ju-Kua, the trade commissioner at Canton in 1226, detailing foreign trade during the Sung, mentioned Ma-i and other exotic place names of a country located “north of Borneo.” Ma-i is without doubt Mindoro, according to William Henry Scott, a leading scholar on pre-Hispanic Philippines. Ma-it, he writes, was “the old name of the island when the Spaniards arrived and in fact is still used these days by hill tribes and fishermen from neighboring villages.” It was “an international entrepôt well situated to control the flow of Chinese products into the archipelago and beyond.” Within 125 years after Chao Ju-Kua wrote his report, Ma-i cloth would become a trade name.

More details on the life of the people of Ma-i compiled during the succeeding dynasties contain the earliest known description of Philippine clothing. A 13th-century book written by a Chinese traveler to the islands notes a shirt made of blue cotton and skirt wrapped around the waist. Another source names that shirt baro, a sleeved, collarless doublet falling slightly below the waist, worn by natives, particularly the Tagalog. The Spanish historian Father Francisco Alcina later confirmed this observation in his unpublished four-volume Historia de las islas e Indios de Bisayas, written in 1668. He says that the Visayans at the time, royalty included, normally wore only a bahag, or G-string, though they covered themselves “against the cold or extreme heat, or the flies and mosquitoes” with a baro, a long-sleeved tunic.

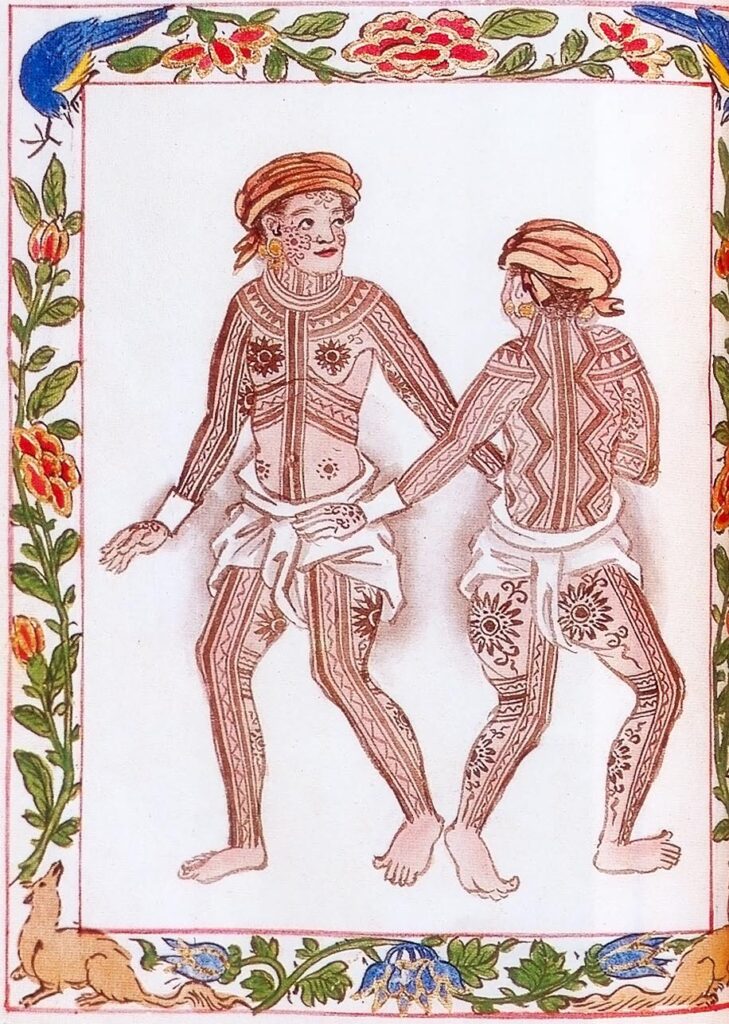

The natives of the archipelago were no naked savages when the Spaniards arrived, or so Antonio Pigafetta, chronicler of the Portuguese voyager Ferdinand Magellan, who in search of the Spice Islands stumbled upon the Philippines in 1521, found out. He was impressed by a datu’s bamboo palace where his host, a picture of sophistication, received him with great pomp. The tribal chief, swaddled in silk and gold and picking on turtle’s eggs served on a porcelain dish, walked his guest to the festive table as music floated from exotic instruments. On another occasion, Siaui, high chief of Butuan and Surigao, came aboard Magellan’s ship, the Trinidad. Pigafetta describes the rajah:

He was very grandly decked out (molto in ordine), and the finest-looking man that we saw among those people. His hair was exceedingly black and hung to his shoulders. He had a covering of silk on his head, and wore two large golden earrings. . . . He wore a cotton cloth all embroidered with silk, which covered him from the waist to the knees. At his side hung a dagger, the haft of which was somewhat long and all of gold, and its scabbard of carved wood. He had three spots of gold on every tooth, and his teeth appeared as if bound with gold. He was perfumed with storax and benzoin. He was tawny and painted (i.e. tattooed) all over.

(Pigafetta in Noone 1968:67 and in Jocano 1975:52)

Nothing surprising there. Recent archaeological finds attest to the existence of lively communities all over the archipelago as far back as 50,000 years ago, dating from the age of the Tabon Caves in Palawan, a habitat of early dwellers.

Across the millennia our ancestors multiplied and settled the main islands. In areas close to the water they established communities called barangay, after the balanghai, boats big enough to carry an entire clan, which they used to explore their island-world.

These communities were substantial in every way. They had tools hewn from stone and iron for hunting and agriculture. Ornaments such as beads expressed their aesthetics. Their use of pottery didn’t just serve simple household needs; their burial jars indicated a connection between their physical environment and the afterlife. They had a system of government, consisting of laws based on tradition and folk belief; their oral literature and alphabet validated their literacy; and they were involved in Southeast Asian commerce through seagoing Chinese and Arab merchants.

It isn’t hard to speculate that from the very beginning the early Filipinos must have worn some form of clothing to protect them from the elements or the demands of hunting and food gathering. Later their rudimentary attire was brought up-to-date by contact with foreign traders. Bartered goods from the Chinese and Arabs included textiles, iron needles and threads as well as articles of clothing like robes and slippers. Besides improving the wardrobe of the Filipinos, these imported items also enhanced their knowledge of ornamentation, such as the use of silk, gold

and silver threads in embroidery, an innovation they picked up from the Chinese, who had been adept at the craft since 3000 B.C. The Chinese and Arabic sense of color and design were also incorporated into native crafts.

These influences, however, merely impressed an overlay on the solid underlay of Malay culture that linked—and still does—the islands of Southeast Asia.

Related Stories

The Barong Tagalog: Personalized and Modern Barong Styles

For one, personalized styles that emerged in different periods are still in vogue. Except for…The Barong Tagalog: From Fibres to Fabrics

Fibers are the building blocks of the yarn; yarns are the building blocks of the…Draping Elegance: Famous Personalities and the Barong Tagalog

The Barong Tagalog, an embodiment of Filipino elegance, has graced the shoulders of numerous notable…The Barong Tagalog: Philippine Presidents

In more recent times the barong fully established its reputation as the national garment. Part…